Dr. Ana Maria Rey, a physics professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, has been named a Laureate for the 2019 Blavatnik National Award for Young Scientists in Physical Sciences & Engineering. In June, The Blavatnik Family Foundation and the New York Academy of Sciences announced the 2019 Blavatnik National Awards Laureates in three disciplines — Life Sciences, and Chemistry.

The award includes a US$250,000 unrestricted prize for Rey’s development of a new understanding of atomic collisions, with direct applications to timekeeping and quantum simulation. Her theory provided a paradigm shift in the precise measurements of time that led directly to the development of the world’s most accurate atomic clock.

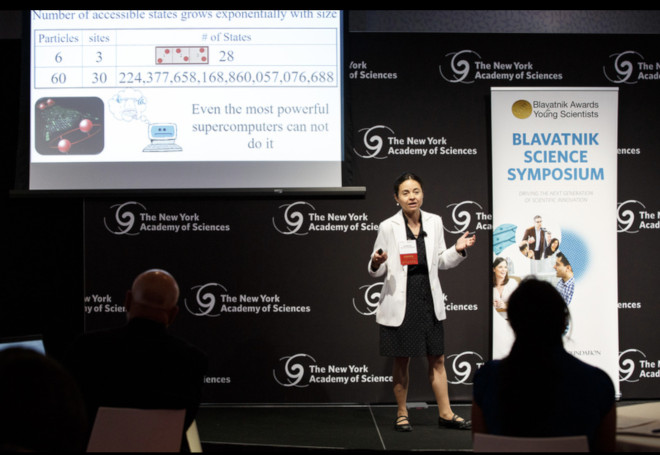

We spoke with her at the Blavatnik Science Symposium in New York City in July.

How has being named a laureate personally impacted you?

My family, friends, and colleagues have been extremely excited. For my family, it was a really wonderful surprise. Back in Colombia, where I am from originally, they have always been incredibly supportive of my work, so I was eager to share this news with them.

For my colleagues, it was like we were all getting the award. My research lab is a continuous collaborative effort, and so it is fantastic for the entire team to be recognized.

How will the Blavatnik Award motivate your ongoing work?

It’s a major motivation for me and my students. We work very hard, and we spend countless hours in the lab, which requires much sacrifice from other important aspects of our lives. As a result, any recognition is a stimulus to ensure we keep up with that work ethic.

More specifically, I hope this recognition motivates other women in science, and it shows that we can make significant contributions to our fields. If anything, it demonstrates that hard work and perseverance can result in achievements. I hope aspiring female students see that.

This is the first year all three laureates are women. Can you expand on how that is significant for you?

It is quite meaningful for me. I think it’s an inspiration because we’re in different fields, and we do different things, but ultimately, we are all women trying to create an impact in the world.It says to me that being a woman—being a mother and having a family—isn’t incompatible with succeeding in your career. I think that message needs to be broadcasted more and more until we have equal representation of women studying and leading in scientific fields.

How will you “pay it forward” from winning the Blavatnik Award?

I want use some of the prize money to start broader discussions about science. I’d like to host seminars every week for students and colleagues to convene, eat pizza, and discuss what is happening in the field.

In the past, I have found that some of the best ideas result from casual conversations rather than in the lab. Continuing to create a comfortable environment for scientists to explore bold ideas is a priority for me.

Why is it important that scientists from other fields collaborate with one another?

We need to bring people together from different fields because science should not be completely siloed, but instead cross-collaborative, in order to achieve the most knowledge. At University of Colorado, we have a Center for Theory of Quantum Matter where we not only have atomic physicists but also high-energy nuclear theorists, so I would like to contribute a seminar series there where scientists can collaborate and learn from each other.

As a Laureate, you were invited to participate in this invite-only Blavatnik Symposium with other leading scientists across all fields. What are you taking away from this experience?

I find it fascinating. I think it’s great to know your field is just a tiny part of science globally, and to hear all these exciting talks on penguins, for example, is just fantastic.

For example, even though I’m an atomic physicist, I am always talking to cosmologists, and that’s important because it allowed me to combine what we know from cosmology to my research.

At the Symposium, I want to explore further ways to incorporate research that’s even farther from my work into my own studies.

Of course, there are many young and mid-career scientists who hope to be a Laureate one day. Do you have any advice for those scientists?

I think the key to being successful is to work very hard at something that you like a lot.

Nothing comes for free, but passion, curiosity, and hard work can lead to wonderful results. You can be very intelligent, but I don’t think that’s enough. You must put time and effort into your goals.

What legacy do you hope to leave behind in your field?

Intellectually, my hope is to develop a new generation of quantum sensors that will have real practical applications. This includes creating the most precise atomic clocks, which should be able to keep exact track of time and impact state-of-the-art navigation and communication technologies. Also, this allows us to explore the secrets of the quantum world and answer fundamental questions about our universe and how nature behaves.

More broadly, I hope to serve as a role model for the next generation of physicists, with particular emphasis on women and Hispanic minorities. I hope to show that they can make a dream come true. It requires hard work and dedication but is possible.